What’s in the Water? For one reason or another, we’ve all had food poisoning. This gut-wrenching, twisty tale almost always begins with unknowingly biting into unrefrigerated or undercooked meat, spoiled dairy products, moldy breads or inedible household items. Often, we rebound in a day or two, vowing never to eat or drink whatever it was again. But what if you couldn’t avoid it?

By Jenna Blyler

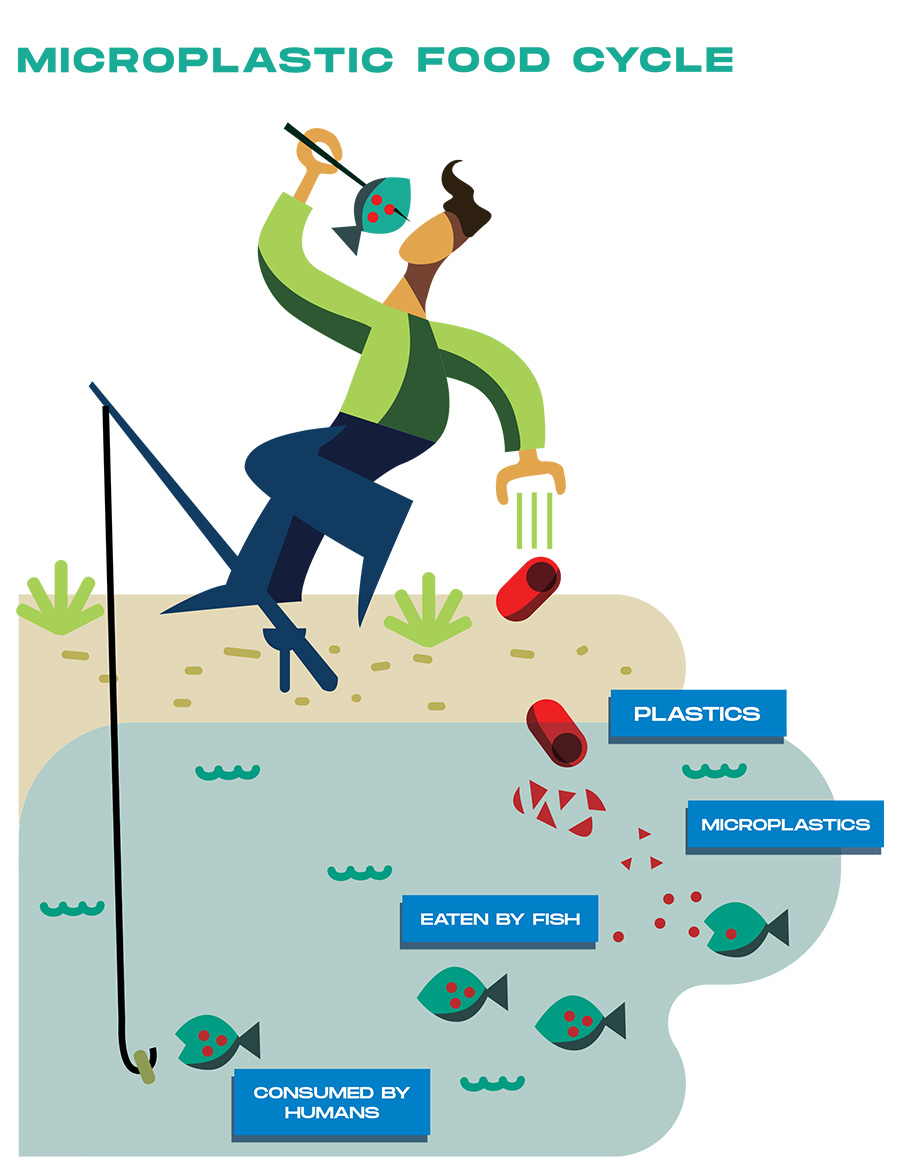

If you think this illness only applies to humans, consider the 400 million tons of chemical and plastic wastes brimming land and sea. Approximately 1.5 billion plastic bottles are purchased daily, 1 million every minute. Research shows that these pollutants are absorbed by various animals, sometimes even as a substitute for their usual food source due to the growing availability of wastes. The uptick in large-scale oil spills, ocean mining, industrial and agricultural waste runoff, chemical spills and species loss has prompted unavoidable questions about what these activities mean for affected wildlife. What are the implications for humans who share the same planet?

Dr. Gretchen Bielmyer-Fraser, environmental toxicologist and professor of chemistry, and her students research the effects of these phenomena on some of the world’s most understudied animals at the Millar Wilson Laboratory for Chemical Research, where she is the director.

“When I was in graduate school 20 years ago, plastics and microplastics, even in the field of toxicology, were rarely discussed,” Bielmyer-Fraser said. “Now, these toxicants contaminate our water, soil and the air we breathe, and so there is a great need to study their effects on humans and wildlife.”

Bielmyer-Fraser came to Jacksonville University in 2016 with more than 10 years of experience as a scientist and professor. Now she directs the University’s undergraduate research program and coauthors the annual St. Johns River Report, which she has done since its start in 2008. In the report, her role is to evaluate the river’s health by examining various indicators related to water quality and contaminants.

Metals like copper, lead, mercury, nickel, silver and zinc, along with various plastics, are extensively employed in industrial processes, technologies, building materials and agriculture. Copper is commonly used in electrical wiring and plumbing, while zinc is found in galvanized steel for construction. These metals are also present in pesticides, fertilizers and animal feed supplements.

When introduced to water through rainfall or direct disposal by businesses, these materials pose risks of poisoning fish and wildlife, contaminating food sources and damaging habitats. Microplastics and chemicals are absorbed by fish and other animals, and when humans eat the animals, they inherit the toxins. Extensive studies are being conducted worldwide to understand the impact of microplastics on human health, but some preliminary evidence shows that exposure can cause oxidative stress, neurotoxicity, reproductive toxicity and a weak immune system.

Habitat loss, however, is the primary threat to wildlife survival in the United States. Pollutants concentrate in the rivers, lakes and wetlands and contaminate estuaries and the food web. This directly influences agribusiness, fishing and tourism.

Despite the importance of these materials in modern society, understanding and monitoring their usage and disposal are critical in minimizing their environmental impact.

Thus, year-round, Bielmyer-Fraser and her team of undergraduate and graduate students conduct extensive fieldwork along the east coast and the St. Johns River, and some travel internationally. Equipped with sampling instruments and meters for salinity, pH, they study the accumulation of these materials in sensitive aquatic species such as sea anemones, fish and coral, as well as top predators such as dolphins and sharks.

Their fieldwork is then transformed into manuscripts, conference presentations, graduate theses and policymaking to prepare students for advanced studies. “Research opportunities are vital for students to gain firsthand knowledge of the scientific method, develop critical thinking and data interpretation skills, and strengthen their writing and communication. I love to see students progress and become more competent research scientists through this process,” said Bielmyer-Fraser.

They apply their findings to protecting understudied species by evaluating current government toxicity guidelines, providing new data and making recommendations. This work is critical to the continuation of many species because — without sufficient data — whole groups could become extinct in the approximately 20 years it takes for standards to be updated. She and her students also use 3D EnviroScape models to demonstrate to school groups and community stakeholders how pollution affects cities and waterways.

In a current study on white sharks in collaboration with OCEARCH, Bielmyer-Fraser discovered that while white sharks accumulate metals in their muscle tissue, they possess effective antioxidant enzymes to detoxify these contaminants, indicating good health. This paper is the first to document metal concentrations in the muscle of white sharks. Her ongoing research also reveals metal accumulation and microplastic ingestion in dolphins and sea anemones, but the long-term effects are still under investigation.

The Millar Wilson Laboratory for Chemical Research is a leading space for dozens of studies every year, but as the researchers analyze their findings and findings lead to more questions, certain waste reduction practices are indisputably helpful in reducing pollutants. These include recycling plastics, using reusable grocery bags, cups and straws, replacing fertilizer with composted organic waste, purchasing secondhand items and donating unwanted belongings.

“Nature is resilient and can withstand some of the contaminants produced by modern societies,” Bielmyer-Fraser said. “However, we all need to be mindful of our waste so that it does not deplete the natural resources that we all love. Education is an important part of caring for the environment.”